About My Father… The Worker Mohammad and the Officers of the Republic

Ahmed AbdelHalim

Translated by Nour Taha

Originally published on 13/08/2024, in عن والدي.. العامل محمد وضباط الجمهورية | خطــــــــــــ٣٠

In half a loaf of bread, Habiba, my mother placed a mix of beans, falafel, and tomatoes along with a cup of tea. It was after 10 a.m. Suddenly, from my room, I heard a thud on the floor. I left my loaf and quickly got up from my bed. I wasn’t scared; I was used to such sounds. I found him lying on the floor. Hala and Mohammad, my sister Raghda's children, were watching. “He was eating, and suddenly he fell to the ground,” Raghda said about the incident. Habiba helped me lift him. Again, we placed him on the bed. Because he had difficulty swallowing food, he began to choke. I was accustomed to such choking episodes.

On the bed, I leaned his head back, then opened his mouth to remove any remaining food. This, I thought, was the reason for the choking. I found no food, and his head stopped moving. I turned it right and left. I rubbed his chest with my hands, but there was no movement. I thought he was dead.

“Dad, answer us,” Raghda said in shock, and began crying, thinking he was dead. “What’s wrong, Mohammad? Quickly, a glass of water, Raghda. He’s dead, he’s dead.” Habiba thought so too. Hala started crying, and Mohammad tried to revive him, thinking he was dead. “Quickly, call your husband; he should come with his car, and we’ll go to the hospital,” Raghda said. In less than five minutes, Ahmed, her husband, arrived. “Instead of going to the hospital, I’ll bring the doctor here,” he said, moving his body. He thought he was dead. We waited, and the waiting ended. The doctor came and confirmed it: he was dead.

To the sound of verses from the Quran, my father's body was laid out, naked. I brought a white sheet to cover his private parts, and those around him circled, looking and examining. In the background, the sound of the Quran reciter accompanied the sobs, the crying, the wailing, with some trying to hush it. The water heater was broken, so I heated the water on the stove. It was one of the days in March 2019. Does the temperature of the water matter to the dead body? Of course not, but this was a time that went beyond mathematical calculations. This was a time of shock, of death.

Around me, my mother moved, and with her hands, she comforted me. The background music focused on the sound of my uncle’s sobs. Quickly, sadness colored the faces of my aunts, Nahla, Naima, and Fatima, in the order of how they were dear to me. Raghda looked at me. Her husband was helping with the burial procedures, as required by the state when it loses one of its owned bodies. Ayman (my brother) called and told us that he would come from the Gulf the next morning.

My father remained silent, smiling, dead, watching us for the last time. A smiling corpse watching those around it.

And I watched him as a body laid out, its flesh, after hours, would be hidden by the earth. I was silent, ordinary. I didn’t mourn his death. Death doesn’t spare anyone. His death symbolized a freedom from the suffering of illness that had never spared him for a single day. When he died in front of me, I stood coldly, looked, and then spoke normally. I do not blame myself for death; it takes whom it takes in front of me until it takes me.

The Gold of Iraq, the Wood of Damietta, and the Illusions of the State

Since his youth, my father, Mohammad, had mastered the craft of shoemaking, a profession he inherited from his father and worked in alongside my uncle Ahmed. My namesake: he is a few years younger than my father. In the early 1990s, my father returned from Iraq, fleeing, empty-handed, from the siege and lack of money, just like tens of thousands of Egyptian workers who had traveled since the mid-1970s and the early 1980s to work in the Gulf states and Iraq. This was due to the labor-export policies sponsored by the Egyptian regime, alongside the policies of economic liberalization, privatization, and the state’s abandonment of its role in providing social welfare to its citizens, instead exporting them as labor to the oil-rich, Petro-dollar countries, which in turn sent back hard currency (dollars) to support their families in Egypt. As a result, a class boom occurred among many of the middle and lower-middle classes, elevating their living standards to above average. According to writer Mohamed Naeem, in his history of individualism and the hustle, this led to the disappearance of clear distinctions between social classes. Yet, my father remained the same; he traveled and returned, and our social class did not change.

Despite his marginal role, my father participated in both the virtues and vices of this country's history, both pivotal, when he and his peers traveled to the Gulf and Iraq in the 1970s, following the oil boom. The country relied on remittances from abroad and benefitted from the exchange rate difference. The economy revived, as did the black market economy, in a strange paradox. The game went as follows: petrodollars flooded the Egyptian market. Remittances from Egyptians abroad were exchanged on the black market at a higher rate, creating a pattern for making easy money, validating President Sadat's saying in one of his speeches, which, in one way or another, encouraged looting: "If you don’t get rich under my reign, you’ll never become rich."

For example, in 1976, the actual price of the dollar was five times higher than the official rate. By the late 1970s, the dual exchange rate system was abandoned due to the massive amount of dollar currency circulating in the local economy. The issuance of the national currency also expanded to meet the demand for withdrawals from the black market, and Egypt’s treasury flourished from those remittances, as the country became, in the words of Tunisian intellectual Ali al-Qadri in his book "Deconstructing Arab Socialism," a fully rentier state after applying the open-door economic policy.

The remittances of my father and his peers, who made up 15% of the labor force in the Gulf, were one of the three pillars that the state built its foundation on, alongside revenues from the Suez Canal and oil. The state was in a state of near death. The state became sluggish, even submitting itself to laziness, to the point where some economists, like Galal Amin, called it "the bloated state," as mentioned by Samer Suleiman in his book "The Strong System and the Weak State." When that source of remittances ran dry in the mid-1980s, due to the drop in oil prices, the state was on the verge of bankruptcy and bowed to the Paris Club in 1987.

Economically, workers abroad were like the goose that laid golden eggs. While Egypt was facing an economic crisis, they managed to provide 3 billion dollars in 1989. The Egyptian government didn’t just rely on remittances; it imposed a tax on the income of Egyptians abroad, which seemed like more of a levy than a tax. Through this, the state was able to collect 240 million Egyptian pounds in four years from Law 228, which imposed a tax on Egyptians abroad, before the Constitutional Court ruled it unconstitutional in 1993.

Between the lines of tragedy for Egyptian workers abroad, you also find a sort of farce, as seen in news headlines from 2023, which talked about meetings between the Egyptian and Iraqi governments to settle the dues of Egyptian workers in Iraq during the sanctions and the war, when Saddam Hussein decided to freeze 1.7 billion dollars deposited in government banks during the siege of Iraq. This means that after 33 years, some died—including my father—and others were born, some workers and their children now aging, and yet their government is still discussing and negotiating the issue of their frozen funds.

Egyptian poet Abdel Rahman Al-Abnudi eloquently talks about this issue in his poem "Arab Colonialism," saying:

“Father, after they humiliated us,

They took the pennies of the poor and kept torturing us,

They drank the sweat of the years and planted the fields,

And sold in the auction our broken back,

I found myself returning to Egypt,

Limping, with a weeping heart,

And Mabrouka in my hand, groaning from the pain,

I said to Mabrouka, 'Surely Saddam didn’t feel it,'

They hid the story from him… you know?

I don’t think so,

And my government, in these matters, is used to ignoring,

Not because it enjoys making me taste humiliation,

But it sacrifices me for the greater good of the nation.”

But at least my father returned empty-handed, not in one of the flying coffins, not wearing a short galabiya, holding a fan in his hand, and without even a Wahhabi vision of life, so no one would attribute to him the sin of the Wahhabi invasion of Egypt.

What matters is that he returned. After his return, he and my uncle continued working together in the shoe-making business, but neither of them was ambitious enough to expand the business, so they met with losses and stagnation.

In early 2005, after all the statues of Saddam Hussein had been toppled, my uncle, who was the youngest of my uncles, had started focusing on the furniture trade. Unlike his brothers, he expanded his business. He worked hard to grow his enterprise. Instead of unemployment, my father had to work with him, or, more accurately, for him. The older brother worked as a laborer for the younger brother. In society’s view, it was an embarrassing and degrading job. I would even tell my friends that my father worked with him, not for him. My father, to some extent, was embarrassed to admit this.

The work wasn’t easy. My father, as time passed, became more and more dependent on the business. He assembled, loaded, traveled, and collected money. That’s how he started early in the day and ended late. During his difficult times, I always heard him say, “I work as a carrier for all of you.” We would hear it and remain silent, so as not to provoke his irritation.

My uncle expanded his business, owning more than one furniture store, several plots of land, a few residential apartments, and one or two cars. He became respected in the area he expanded into, with his name ringing of reputation and fame, earning everyone’s respect —merchants, beggars, families, and even the miscreants and those on the margins of society. People would always ask me when they learned I was from this family, “Is Hajj Sayed your relative, the furniture trader or the drug dealer?” I’d reply, “The furniture trader, the drug dealer is also a relative, but from a distance.”

Our family included those known for drug dealing and thuggery. Sometimes, I would use my affiliation with them for protection, to avoid the bullying of others, whether at school, on the streets, or even in political prisons.

A General, Craftsman, and Workshop Master

Less than half a century has passed since these memories, yet when I talk about Damietta, my uncle, the workshops, and furniture-making, I feel like I’m talking about the ruins of a city and the ghosts of people who were once here and have disappeared. Yes, Damietta is the coastal city located in the north of Egypt, where the Nile meets the Mediterranean Sea. It spans an area of 910 km² and has a population of nearly 2 million. It was once famous for several decades as the heart of Egypt’s furniture industry, and perhaps the Arab world as well. The city was buzzing day and night with work inside small workshops, and anyone who specialized in a particular craft and excelled in it was almost considered as accomplished as a doctor or an engineer in the eyes of society.

Damietta and its people resembled that atmosphere and mindset before it became "Damietta: The Furniture City," a showy city similar to Persepolis, the ruins that tempted the Shah of Iran to host a medieval grand celebration in 1971 while his people were starving, to witness his false glory. Likewise, "Damietta: The Furniture City" destroyed "the furniture of Damietta." Up until 2014, Damietta was one of the least impoverished cities in Egypt, with only two other non-populated governorates, the Red Sea and Suez, ahead of it. The poverty rate was 10%, but now, after ten years of supposed "achievements" and "modernizations," it has increased to 15%.

Damietta used to serve the furniture industry across all of Egypt’s governorates. Exhibitions in Cairo and Qalyubia worked with the city’s carpenters to bring in raw sets of furniture, which were then prepared in workshops in Cairo. Now, the craft is no longer sufficient for the city's residents, who have only received legal challenges for their inability to pay rent for their shops. Many extravagant international exhibitions no longer attract visitors, and the president’s smile when he spoke about them remains a distant memory. Unexpectedly, he accused them, the people of Damietta, of laziness.

The first time was in 2019 when he said, "What is up with people from Damietta? Don’t you have dreams? Has everyone stopped dreaming?" And again, in 2022, when he lamented his grand project, calling it unsuitable for the social environment and blaming laziness: "The people of Damietta didn’t go to work in the city because they’re used to having workshops under their homes." The president dreamed of making Damietta: The Furniture City global, but due to the lack of feasibility studies, he turned into a man who, every time he touched gold, turned it into dust. In 2017, the city was exporting goods worth $270 million, only for the value to decrease to $170 million by 2022.

The state didn’t just kill the furniture industry in Damietta through its grandiose project, but it also destroyed it by deteriorating the economic situation in the country. This was evident in numerous devaluations of the Egyptian pound, which made the local currency extremely fragile, especially for importing necessary materials for the industry, whether it was wood, chemicals, or even brushes and putty knives. The artisans and the informal economy were left exposed, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, which worsened their already dire situation without any social security coverage.

While the president dreamed of turning Damietta into a global furniture hub, even the local customers abandoned it, as the craftsmen turned to tuk-tuks, food businesses, or working as security guards. Nobody benefited from this except for the lawyers handling the cases of the poor workshop owners who were imprisoned for failing to pay rent. In reality, they were more deserving of breaking the contracts, as the company that provided them with the workshops should have been responsible for paying the bank on their behalf. This is how Damietta was, and how it became.

As for my father, since he started working with, or rather at, my uncle's workshop, which always irritated him, he would leave the work countless times, both frequently and intermittently. He would come home angry, cursing everything around him. We would ask him, "What happened?" He would reply angrily, "Damn poverty, need, hunger, and Israel," before locking himself in his room, pretending to sleep, his eye full of tears, his pockets empty.

The reasons were simple. In front of the people, my uncle Said, would call him Mohammad, instead of Abu Ayman. In front of the people, if there was a problem, he would raise his voice at his older brother. If there was a problem between my father and one of the workers at the exhibition, my uncle would testify against my father. These were the reasons, all of them revolving around my father’s dignity, and he was right. Is it not enough that his dignity is violated everywhere? Even by his brother? Is it not enough that the state and its notorious security apparatus trample on his dignity, along with millions like him?

At that time, I was a small child with no say in the matter. I was in elementary, middle, and high school, and early university years. When facing these problems, I stood by my father. I hated what my uncle did, despite him being a kind-hearted man, especially since I held a special place in his heart. After a few days, my uncle would come to the house, accompanied by someone who my father held in high regard. Then reconciliation would occur, and everything would return to the norm—vain and unjust.

I used to reproach my uncle for what he did, and what made me even more repelled was that my father's weekly wage was minimal. In fact, my wages as a young man working in the workshop were larger than his. My uncle didn’t appreciate the expenses of the family—three children, school and university fees, my sister’s wedding preparations, food, drink, and medical costs. My father’s wages were equal to the allowance of a small child. If it weren’t for the salary of Habiba, the family would have fallen apart, as she worked in the local municipal council. She managed the household finances strategically—loans from the bank, cooperatives with friends, and borrowing from neighbors. These were the solutions. We, like hundreds of thousands of families, lived on loans. I will never forget the times, countless times, when my mother, with an embarrassed face, would step out in the mornings before school, hesitating between steps, knocking on our neighbor’s door to borrow 10 or 20 pounds, and then return, trying to hide her embarrassment, and give me and my siblings the money to buy sandwiches for breakfast, so we wouldn’t go to school with empty stomachs. Often our house, like many of our neighbours, if turned upside down, would drop a single penny.

Many would not consider my mother a breadwinner, though she was. Despite having a husband and two sons, she was counted among Egypt’s 3 million women breadwinners in a country of 23 million households, according to the latest official census in 2017. This number has certainly grown since then. The census defines the female breadwinner narrowly, excluding others like my mother, who, although she had a working husband and two sons who weren’t yet of working age, contributed the majority of the household income. These women are the most affected by what is called "economic reform" and its successive austerity decisions, which began under Sadat’s rule and continued under Sisi.

This is confirmed by statistics, despite the government’s claims of having a program to uplift female breadwinners, in addition to economic empowerment programs for them. However, a study on income and spending between 2019 and 2020 showed that 16% of households led by women are living below the extreme poverty line, and 41% are below the national poverty line, numbers that far exceed the percentages for households led by men. These statistics do not include women like my mother and others who are considered breadwinners.

The Illusions of Masculinity, Revolution, and Exile

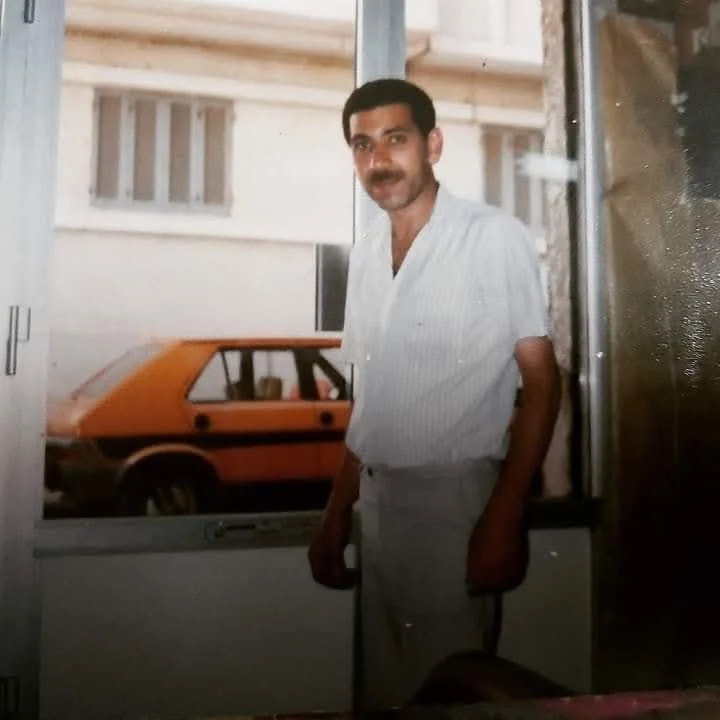

As for the creation made by God, my father was handsome, with a slender frame, an average height, and light green eyes on a fair face, topped with short, coarse black hair, ending in the complete whiteness from illness and poverty. He was a man who wore simple clothes—plain and dark, like the clothes I wear now. A few fabric pants under button up shirts and T-shirts with collars, and on his feet, either slippers or ordinary shoes.

Mohammad was more beautiful than Habiba. In her youth, some of her features resembled the Egyptian actress Shadia—her dark hair, eyes, and fair face with calm features marked by intelligence. My aunts, Fatima, Nahla, and Naima, always joked with her, teasing her about Mohammad’s handsomeness in comparison to hers: "If you traveled the entire world, you wouldn’t find anyone as handsome as him," they’d provoke her. "Oh really, he’s a catch, but he turned out to be a fool," she’d laugh and argue with them.

My father, like many Egyptians raised during the years of the Free Officers' Republic, who seized power and turned it into a space of exchange and conflict among them, never seized anything. He was illiterate, dropping out of school in the first grade of primary school. The behind-the-scenes story is that a cart pulled by two donkeys ran over his leg, leaving a scar that marked his body until death, preventing him from returning to school. The false reason was that his family, like many others, didn’t care about education. My aunts had a middle school education or above, while my uncles, Ahmed and Ayman, like my father, were illiterate. Uncle Sayed was the only one who learned to read and write before dropping out after the third year of middle school.

Cursing, criticizing everything, analyzing all events and matters, supporting dictatorships, glorifying Nasser, Gaddafi, and Saddam—my father even intended to name me Saddam. At that time, he had just returned from the Iraq siege, which had just ended its occupation of Kuwait, but before my birth, my cousin Ahmed died young, and his name was Ahmed. Since he died, the next child was to be named Ahmed. This is how followers name their children—after other deceased followers, not after kings or gods of power and love. Thus, my cousin's death saved my name.

Apparently, the love for Saddam was not unique to my father. This man lived in a country where Saddam occupied all the public space, taking over every inch without exception. Saddam’s images, statues, and portraits were everywhere—in streets, offices, schools, squares, radios, televisions, memorials, and even in the homes of the poor during surprise inspections of their refrigerators to check whether they were full or empty. The poor Tikriti child who was born into poverty became the leader of his people, was executed by his enemies and enemies of humanity, and surrounded by the aura of prophecy! Pictures of Saddam fill the mind: once in tribal Arab attire and with a sword, another in military khaki, and yet another in an “ushanka” hat, the hat of the red communist struggle, or in a British hat, an Oxford suit with a Kalashnikov in his hand, with his rough voice and his fake Baghdad accent. Saddam, Nasser, and those like them were "macho men" in my father's and his generation's minds, and many other generations would come to glorify them. According to the Lebanese writer May Ghassoub in her study on imagined masculinity, “They represent everything for an Eastern man who feels defeated and wounded in his masculinity.” Through political oppression, they identify with the oppressors.

People such as my father had support for dictatorships, and adopted regressive practices regarding men, women, trans people, children, and the elderly—haram and halal, shame and duty, and so on. When these people's tongues move, they only show a lack of everything, the first being knowledge and the last being morals. Among them was my father. I don’t mean to distance him from anything related to knowledge or morals—he knew, and he was ignorant of both, just like everyone else. Everyone knows and ignores, everyone is neither black or white, but everyone believes in the “whiteness.”

Regarding my father’s "whiteness," when I was a child, I used to ride the bike he borrowed from a friend named Ihab. I remember him well. He worked as a coffee seller and often brought me freshly squeezed orange juice without charging my father. On the way to the hospital, which was next to my uncle’s exhibition, the trip by bike took about fifteen minutes from home. To strengthen my immunity against diseases, I used to get an incredibly painful injection called the "long-term injection," which was taken every two weeks. Afterward, I would cry from the pain, and my father would embrace me to soothe the pain and stop the crying. With a smile, he would offer me a choice: "Would you like to drink sugar cane juice or apple juice?" I’d choose, drink, and the pain would go away. Sometimes, he would buy the juice with the last pound in his pocket, but it didn’t matter to him. Despite his poverty, my father was rich in generosity and never bought cheap, faded goods to save money—he bought the expensive ones without caring about going bankrupt.

This is how my father was. If he had known, if he had learned, he would have written to me as a writer: "Ahmed, how are you? You are afar, you’ve been exiled, don’t despair, I’ve lived afar too, as a follower, an expatriate, and when I returned, I was even poorer and more afraid. But tell me, how is poverty with you? Have you managed to rid yourself of it, or did you fail like me? I know you love reading and writing, I saw you write before I died. At least you managed to escape from the line, from ignorance—you were not run over by the karu! You were run over by other carts, the carts of power, prison, and exile. What matters is that you know I love you, and I know you love me, I saw this from you in many quiet moments. Or at least you loved my back, which lived and died bent because of poverty and illness."

And I would reply, with longing to embrace his body, his remains even, saying, “My father Ayman, don’t worry... I love you, and you know that even if I were a magician, a prophet, or a god, I would never have thought to make you an engineer, a doctor, or even a king who rules the earth. I would have left you as you are, Mohammad the worker, the follower, whom I wished to be alive when I could have secured your fear, eliminated your poverty, and lifted your back. But life is like this, terrifying, humiliating. And I, my beloved, assure you that I revolted against those who caused your alienation, fear, and poverty, and they are gone. But soon enough, another officer came, a tyrant, another killer, who made me poorer, imprisoned me, and chased me until I became a fugitive, an exile, and now I write about me, about you—we are the children of oppressive regimes.”

In his youth, my father left his country searching for a living, and in my youth, I left prison and fled the country, just to live. We, the youth of Egypt, in our revolution and defeat, failed. We don’t have a "political diaspora," no lobbying group, no political project anywhere in the world. Can you imagine, for example, that we could convince the "neoconservatives" to come invade our country to liberate it from oppression, as Ahmed Chalabi and Kanan Makiya did before us in Iraq? We just fled to the nearest place we could. I traveled to Lebanon by plane through airports, because I was involved in politics, prison, culture, and human rights, and found this escape route.

But others, especially from Damietta and Egyptians in general, decided to cross the sea searching for a safe haven. Some died at sea, some died in Lampedusa, and some managed to reach Athens and Milan after having to cross a real death journey—after paying $10,000—in the Egyptian deserts first, to reach Libya and then there to migrate. Yes, migration to Libya first, because it is the current route, as the Egyptian authorities receive funds from the European Union to play the role of guarding the Mediterranean Sea and preventing illegal migration. But in return, they facilitate their migration to Libya to rid themselves of the burden and benefit from their money if they reach their refuge. They are like my father forty years ago, a golden egg. Egyptian remittances from abroad will continue to save this country until the Day of Resurrection. They are like me too—every escape from this country called Egypt was because of politics.

No Care For The Urban Mob

My father's illness deteriorated before it killed him. For three years, Habiba and I took him to physical therapy sessions. The last months, before his death, were extremely difficult. My father couldn’t walk, couldn’t speak, couldn’t eat—he lived on fluids, and listened to Umm Kulthum, Warda, and Abdel Halim Hafez. He lived blending in, like any ordinary follower, watching their concerts on TV. All his life, he sat listening to them, blending in and listening. This was how he repeated his usual evening at home.

From the third floor, Habiba and I would carry him up and down. Sometimes, my uncle Sayed would come to carry him and drive him, other times, our neighbor Mohamed El-Sayed would come to carry him and drive him, and sometimes, rarely, my friend Magdy would come to carry him but could not drive, as he was poor like us and didn’t own a car. Three times a week, we would go to the physical therapy center.

But I wonder if my father, in another story, could have lived longer and healthier if successive governments had viewed at the handicraft sector and informal economy workers as citizens? For decades, governments have boasted about what they do for public sector employees and to a lesser degree, for private sector employees. Pay raises, pension systems, healthcare, and state hospital treatment, while my father and nearly 13 million workers had to suffer from price hikes without pay increases, illness without health insurance, and no affordable and proper medical treatment—just numbers counted by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, which has created a crisis due to their lack of family planning. Here, the government only remembers them because of their ignorance and their need for cultural reform.

The parallel Egyptian economy lured Egyptians after the period of economic liberalization, making many of them give up education and the dream of working in the state, which was already retreating in its role in building factories and employing people and neglecting its developmental role while expanding the labor market. Many of the self-employed workers were not factory owners or from the "small bourgeoisie" but were closer to the proletariat, lacking access to paid labor, so they had to work for themselves in hopes of earning enough for their families’ basic consumption needs, as economic researcher Amr Adly pointed out.

They formed one of the most vulnerable groups lacking social protection, so my father never dreamed of free treatment in a government hospital, nor did we ever seek treatment at the state's expense. They worked in informal relationships, not governed by labor law, nor do they have insurance protection or job security. They also require significant effort to be controlled by the system of oppression, as they form the despised "urban mob," as British geographer David Harvey calls them.

Even though they played an important role in the struggle against neoliberal savagery, some Marxist literature looks at them with more fear than adoption of their struggle, which is the spark for uprisings against the capitalist system and dictatorship, such as the 1977 bread uprising, which was launched by labor unions but ignited thanks to these marginalized, insecure people, and also in the January 2011 revolution, and the subsequent revolutionary upheavals, especially during the Mohamed Mahmoud events, and in any revolution that will come.

As for my father, this newly disabled man, one evening during his final days, Habiba and I came back from the physical therapy sessions, and at the bathroom door, I tried to push his body to get him in. “Baba, baba, listen, try to walk, don’t pretend, don’t fake the tiredness to get better,” I bargained with him. With similar words, I repeated my attempt, until I started cursing: “Baba, fuck, damn this role you're playing.” Then Habiba carried and supported his walking device. “Calm down, calm down, walk yourself, I will support you,” she said as though irritated with me. I stayed silent. “Shame on you, son. Walk, walk. Shame on you,” Habiba replied to my silence.

Habiba felt very sorry for my father. She really felt he was suffering, and specifically this time, he wasn’t lying. It was me who was deceived, driven by tension. The illness didn’t only stop him from eating; it consumed his mind, turned him into a child who couldn’t understand. He lied for no reason, laughed, and played. My father always wanted us to carry him, to be with him, and never be out of his sight. He would toy with us, pretending to be tired just for the sake of his interaction with us, as if saying to himself, "I lived all my life as a follower, marginalized, and now in the last days of my life, I want to be seen."

At that moment, I thought he was pretending. I was ungrateful, wrong, and still am. Which one of us is an angel? Then I went out of the house to the café, as usual, to meet my friends, fellow fugitives from prison and poverty.

Oppression is Another Kind of Death

Under the current regime and its new republic, I was sentenced to five years in prison. I spent two years of that sentence in the highly secure prisons of Gamasa and Port Said, before being released by the Court of Cassation, which accepted the time I had already served. In late 2014, I was arrested after one of the protests against the regime’s continued crackdowns on its political opponents. Several charges were fabricated against me, including joining in a banned organization (I still don't know what that organization that is!), disrupting public life, destabilizing the government, and protesting without permission—like tens of thousands of political prisoners in Egypt, due to my opposition to repression, its representations through killing, imprisonment, enforced disappearance, and other forms of torture that the regime has imposed on the Egyptian people since July 2013, affecting all segments of society—regardless of their thoughts, ages, or affiliations.

This was my reality, along with thousands of Egyptians of all kinds, ages, and classes—prisoners charged with fabricated accusations such as spreading false news, joining a banned organization, protesting without permission, and disrupting public life. These false charges swallowed us into prisons that slowly kill us. What kept us alive throughout these long years were the few minutes each week or two when our friends and loved ones visited us.

As for my father, before illness took its toll on him, he was, with great vitality, under the scorching sun and biting cold of my prison years, coming to visit me, bringing bags of food, drinks, and clothes.

In the middle of it all, I was between them — Habiba on my right and my father on my left, or vice versa. Habiba was always chatty, telling me about the family scenes, the friends, the study, the lawyers, the expenses, and life. As for him, during the visit, his words were simple and cut through his silence: "Thank God, they send their regards to you, take care of yourself." This, and a simple laugh.

Once, he broke his silence and asked me if I knew a person named Ashraf (and mentioned his last name), his cousin, who had been imprisoned for over fifteen years for crimes related to murder and drugs. "I’ve never seen him," I replied. "I’m in a section full of political prisoners," I explained. I then remembered and added, "But I met his son, Osama, in Port Said prison." He responded wisely, "May God relieve their hardship." Habiba interrupted us, sarcastically smacking her lips: "Wow, I’m so happy your relatives are in prison. It’s a great family connection!"

“Don’t act all high and might with me, sister, you’re lucky you married me,” he replied, and we laughed. Habiba would get annoyed, while he, on the other hand, was proud of his family. He understood that this world values strength over morality, and it boasts about drug abuse rather than politics.

In the last four months of my imprisonment, my father stopped visiting me. He was tired of the prison visitation lines, the humiliation, the fear, and the disgrace, or perhaps he was pained by seeing me as a prisoner, shackled from life, while he was powerless to do anything. After all, how can a follower, a poor worker, resist the authority? Habiba told me he was doing fine, but couldn’t walk anymore. A month earlier, I had noticed his illness; he walked slowly, swaying, and his speech had become heavy: "Thank God, they are tak-ing me to the doc-tor, and I’m not get-ting tre-at-ment yet, th-an-k G-o-d." That’s how he would speak, slowly and brokenly. At the time, they told me that he was under the care of a brain and nerve doctor, due to a stroke he had suffered.

After my release from prison, I thought for a while that my imprisonment had caused his stroke, just as Habiba insisted on planting this thought in my mind, not to blame me for something I hadn't done, but perhaps to convince me to stay away from politics entirely. That’s how families, who fear prison and authority, act. Later, I learned the truth from Ayman and Raghda’s gossip, as they told me that during this period, my father had, as usual, been angry at work because of my uncle, due to a disagreement with one of the workers.

His name was Hajjaj, an old friend of my father’s, whom he had brought to work at the store. However, he did not honor this, and he was stealing, sowing conflict. This is how my father used to describe him. But this time, the sadness didn’t pass without affecting my father, and it caused the blood to freeze in his body. We buried him, and at his funeral, accompanied many of God’s followers, not the government officials or the famous. It was a great scene, and soon I’ll be walking in my own funeral in a country that isn’t mine, where no one will walk in it, not even a follower or a worker like my father.

Ahmed AbdelHalim is an esteemed Egyptian writer and researcher with a specialisation in political sociology, body studies, and the analysis of punitive practices within Egyptian prisons.

Nour Taha is an Egyptian-American researcher, journalist, and translator, currently working as a Research Assistant at the Middle East Democracy Center and as an Editorial Research intern for the Arab Center Washington DC. His research focuses on Democratization and political repression in MENA countries. His work has appeared in prominent outlets such as Middle East Eye, Arabic Post, and Jadaliyya.